Home

Historical ContextPrejudice & DiscriminationThe Stonewall UprisingGay Liberation

Contact Hypothesis

Moving Forward

Resources

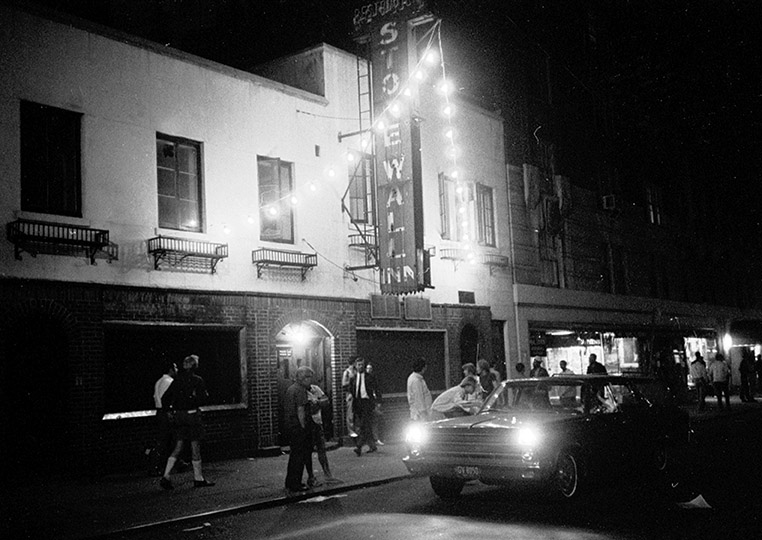

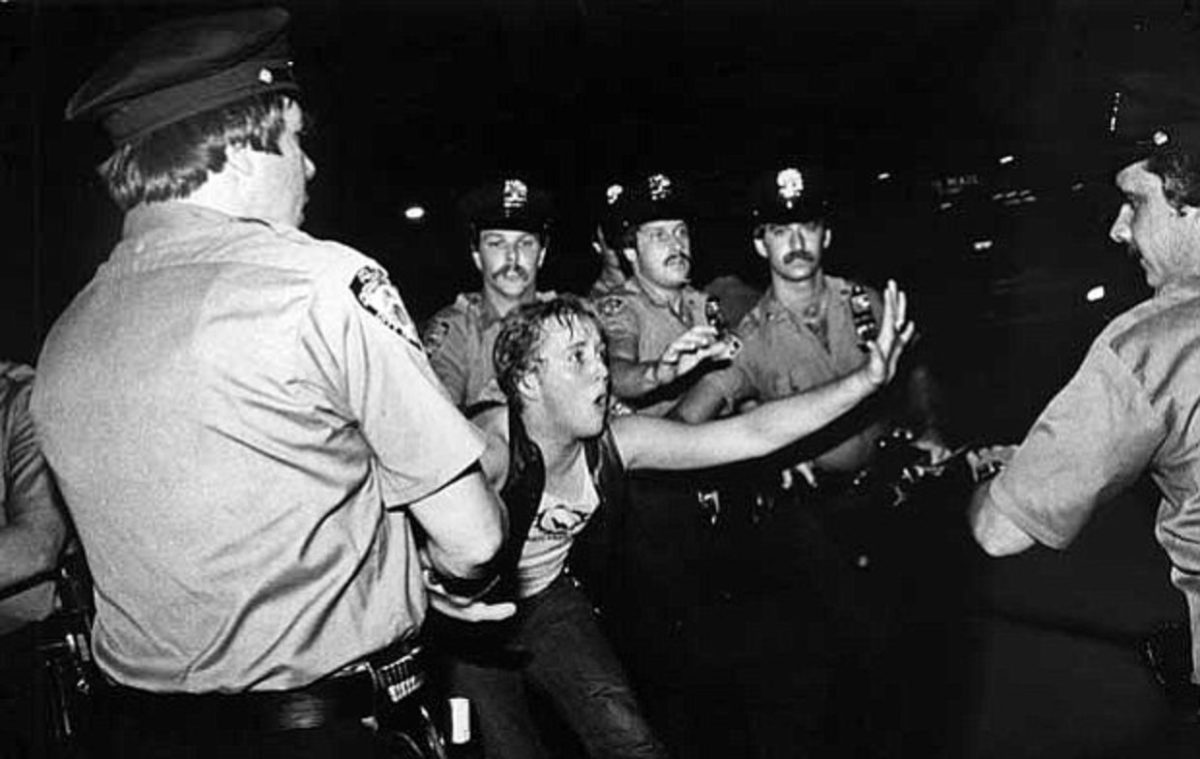

(Stonewall Inn, 1969, by Fred W. McDarrah, The Eye of Photography)

Many individuals of the LGBTQ community were residents of Greenwich Village. Stonewall Inn, a gay bar located in Greenwich Village, was a place of refuge for these individuals.

(Stonewall Inn, July 2, 1969, WordPress)

“There are hundreds of young homosexuals in New York who literally have no home. Most of them are between 16 and 25, and came here from other places without jobs, money or contacts. Many of them are running away from unhappy homes (one boy told us, 'My father called me 'cocksucker so many times, I thought it was my name.'). Another said his parents fought so much over which of them 'made' him a homosexual” (Dick Leitsch)

"The Stonewall operated as a sort of de facto community center for gay youth rendered homeless by familial and institutional rejection, who had taken refuge in New York City in hopes of finding a place where they could be in the world." (Franke-Ruta, 2013)

“According to David Carter, historian and author of Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution, the 'hierarchy of resistance' in the riots began with the homeless or 'street' kids, those young gay men who viewed the Stonewall as the only safe place in their lives.” (Pruitt, 2019)

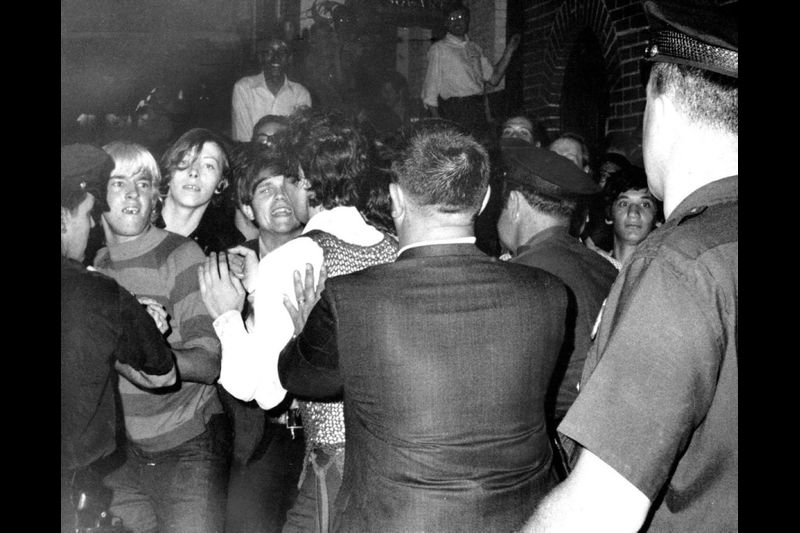

(Impeding crowds, June 28, 1969, by Joseph Ambrosini, New York Daily News)

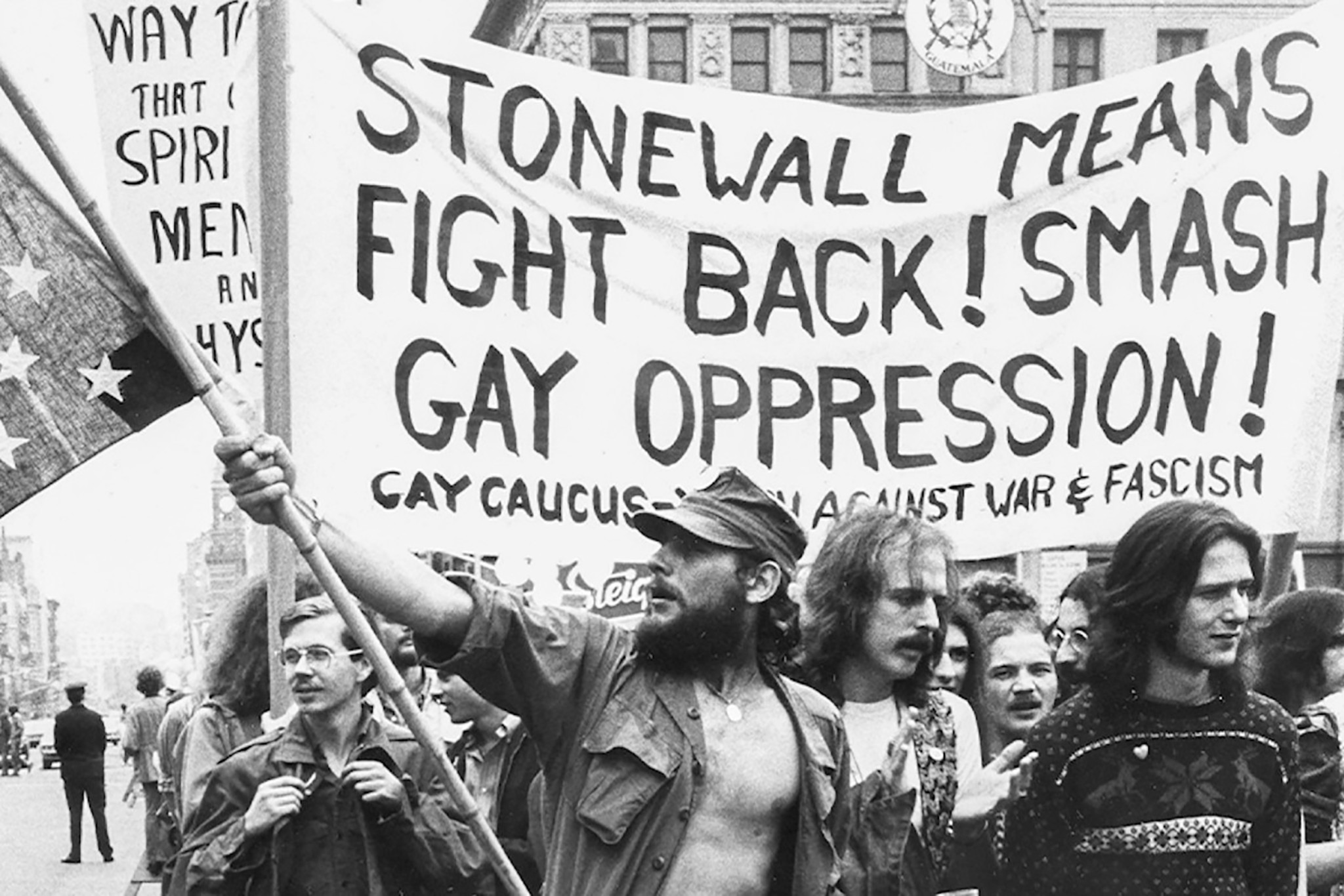

(Protestors in the aftermath of Stonewall Uprising, 1969, The Harvard Gazette)

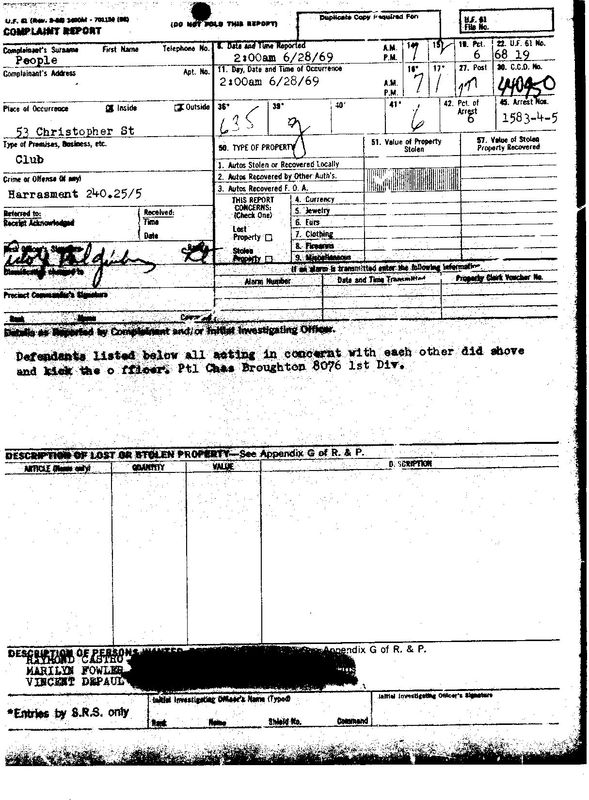

The Stonewall Uprising started the morning of June 28th, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn. Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine led a bar raid, which ignited an outbreak of resistance. The LGBTQ community fought back due to the built-up frustration from the constant mistreatment. The people were tired of the social barriers and inequalities that separated the LGBTQ community from society. The crowd of people formed outside of Stonewall began throwing objects at the police officers, which led them to retreat into the bar. As a result, to control the situation, the Tactical Patrol Force was called, which was the city's riot police. The uprising lasted several days after the raid and cultivated a progressive group of activists leading to the start of the gay liberation movement.

(Open Road Media, 2013, Youtube)

“It would see: fire hoses turned on people in the street, thrown barricades, gay cheerleaders chanting bawdy variants of New York City schoolgirl songs, Rockette-style kick lines in front of the police, the throwing of a firebomb into the bar, a police officer throwing his gun at the mob, cries of ‘occupy—take over, take over,’ ‘Fag power,’ ‘Liberate the bar!’, and 'We're the pink panthers!’, smashed windows, uprooted parking meters, thrown pennies, frightened policemen, angry policemen, arrested Mafiosi, thrown cobblestones, thrown bottles, the singing of ‘We Shall Overcome’ in high camp fashion, and a drag queen hitting a police officer on the head with her purse.” (Franke-Ruta, 2013)

"It was terrifying. It was as bad as any situation that I had met during the army. Had just as much to worry about because they began to throw Molotov cocktails. They began to strip the gasoline, and they began throwing them in through the glass windows that they were able to cut or push through. And we had problems because we had maybe six people, and by this time there were several thousand outside." (Seymour Pine, 2011)

"Whenever one person fires a gun, it sets off a stream, the others can't control what they're firing at or who they're firing at. And so you have six guns and hundreds of people in front of you . . . 'Don't fire until I tell you to fire. Keep backing up until we can't back up anymore.'" (Seymour Pine, 2011)

“Once the TPF arrived at the Stonewall Inn, the mood intensified, and the police tactics quickly became violent. TPF officers were dressed in full riot gear, complete with helmets, body shields, and nightsticks. They began swinging their nightsticks at people, often hitting them on the head. This was called ‘braining’—using a nightstick to strike a person’s head with full force. The goal was either to temporarily stun the victim or to knock then unconscious. As you might imagine, this is dangerous and violent, and the practice sometimes caused concussions, skull fractures, and even death.” (Pitman 61)

"'Up until the night of the police raid there was never any trouble there,' she said. 'The homosexuals minded their own business and never bothered a soul. There were never any fights or hollering, or anything like that. They just wanted to be left alone. I don't know what they did inside, but that's their business. I was never in there myself. It was just awful when the police came. It was like a swarm of hornets attacking a bunch of butterflies.'" (Lisker, 1969)

(Police report, June 28, 1969, OutHistory)

(Police clash with protestor, 1969, PBS)

(New York Daily News newspaper, July 6, 1969, Splinter News)

After the Stonewall Uprising, the media published offensive articles covering the event using derogatory terms against the gay community.

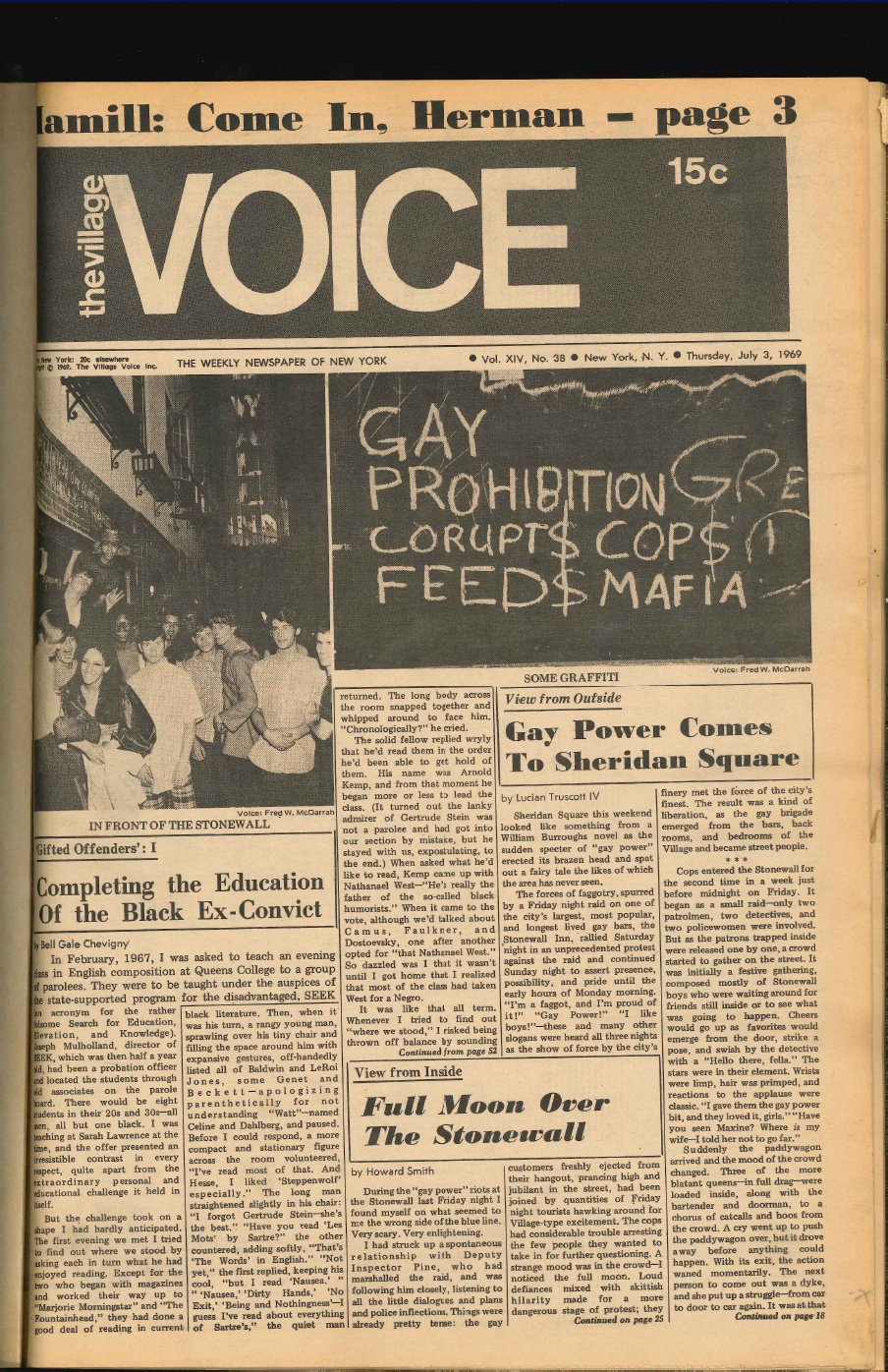

(The Village Voice newspaper, July 3, 1969, WordPress)

“The most striking thing about the media coverage of the Stonewall riots—the 1969 uprising that was a turning point in the gay rights movement—is how offensive much of it was.” (Brockell, 2019)

“Both the Daily News and Village Voice stories were long and detailed, but the focus is on prurient descriptions of gay and transgender people meant to highlight their difference.” (Brockell, 2019)